Back in 2003 I got into a blog tussle with Joi Ito, the disgraced former director of the MIT Media Lab who was forced to resign from the Lab and a number of corporate boards over ethical lapses related to Jeffrey Epstein. I was fairly amazed that Ito was hired by the Media Lab in the first place.

It seems like a job for a futurist, a technologist, or an intellectual, and Ito is none of those things. But he is well-connected, which is great for fundraising if nothing else.

Emergent Democracy

I’m not going to rehash the issues at MIT because they’ve been well covered by Ronan Farrow, Andrew Orlowski, and Evgeny Morozov. I’d like to share a post I wrote about Ito’s ideas about something he called “emergent democracy”, my reaction to them, and Ito’s reaction to my commentary. This is about schadenfreude, in other words.

Ito was one of the first to jump aboard the blog train in the days when we still called blogs “weblogs”. He tried to put together an essay mashing up the ideas Steven Johnson laid out in his 2001 book Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software with Howard Rheingold’s 1993 musings about the Internet in The Virtual Community.

In essence, Ito claimed that the Internet could, given the creation of new tools, revolutionize the ways societies govern themselves. Instead of the musty old top-down, command-and-control model of representative democracy, the Internet could expand the circle of participation in governmental decision-making and usher in a new era of direct democracy.

Since [1993, Rheingold] has been criticized as being naive about his views. This is because the tools and protocols of the Internet have not yet evolved enough to allow the emergence of Internet democracy to create a higher-level order. As these tools evolve we are on the verge of an awakening of the Internet. This awakening will facilitate a political model enabled by technology to support those basic attributes of democracy which have eroded as power has become concentrated within corporations and governments. It is possible that new technologies may enable a higher-level order, which in turn will enable a form of emergent democracy able to manage complex issues and support, change or replace our current representative democracy. It is also possible that new technologies will empower terrorists or totalitarian regimes. These tools will have the ability to either enhance or deteriorate democracy and we must do what is possible to influence the development of the tools for better democracy.

Emergent Democracy, Joi Ito, 2003.

Mixed Results

To Ito’s and Rheingold’s credit, they didn’t see a future that was all peaches and cream. But it was fairly obvious even in those days that the popularization of the Internet was going to bring forth both good and bad results.

We can learn obscure subjects quickly, we can shop at the world’s largest store without leaving our desks, and we can learn how to fix things. But we also have Trump in the White House and a networked terror cult known as ISIS tearing it up in the Middle East.

It wasn’t either/or, it was both/and: new conveniences and new threats at the same time. Ito didn’t anticipate this, but it was always the most likely future. He also found himself unable to complete the essay, so he turned it over to one of his Wellbert friends, Jon Lebkowsky, to finish.

My Criticism

I addressed an early draft of Emergent Democracy in this post, Emergence Fantasies. It appeared to me that Ito was effectively touting a form of government like the California initiative process that would be informed by blog posts and effectively controlled by a blogger elite. The elite bar was pretty low among the blogs in 2003, so this didn’t look like progress to me.

The larger problem was the essential incoherence of Ito’s reasoning. Well-connected as he is socially, Ito is no intellectual. He also lacks a reasonable understanding of the ways legislative bodies work, at least according to my frame of reference as someone who’s been working with them for twenty years or so.

The emergence thing is also suspect. A the time, it was a fixation among the crowd that thinks of Jared Diamond, Steven Pinker, and Nassim Taleb as great thinkers, but it’s little more than trivia about the behavior of animal groups. Ant colonies are far from grass-roots democracies in any case, and they’ve fascinated political thinkers for thousands of years. I’d be happy to read a book on the biochemistry of ant colonies, but Emergence is not it.

So I said this:

Emergent democracy apparently differs from representative democracy by virtue of being unmediated, and is claimed by the author to offer superior solutions to complex social problems because governments don’t scale, or something. Emergent democracy belief requires us to abandon notions of intellectual property and corporations, apparently because such old-fashioned constructs would prevent democratic ants from figuring out where to bury their dead partners, I think. One thing that is clear is that weblogs are an essential tool for bringing emergent democracy to its full development, and another is that the cross-blog debate on the liberation of Iraq is a really cool example of the kind of advanced discourse that will solve all these problems we’ve had over the years as soon as we evolve our tools to the ant colony level.

Emergence fantasies, me, 2003.

The conversation continued on Ito’s blog under a post ironically titled Can we control our lust for power? The answer to that question was obviously “no”.

The Black List

Ito was not amused, so he black-listed me:

Mr. Bennett has a very dismissive and insulting way of engaging and is a good example of “noise” when we talk about the “signal to noise ratio”. Adam has recently taken over the fight for me on my blog. My Bennett filter is now officially on so I won’t link to his site or engage directly with the fellow any more. At moments he seems to have a point, but it’s very tiring engaging with him and I would recommend others from wasting as much time as I have.

So that’s Joi Ito for you: a man who loves Jeffrey Epstein so much that he’s willing to lie to his bosses to keep him in the Media Lab social network but can’t take honest criticism. His fall from grace was long overdue, and I’m proud to have such enemies.

st a batch once a week or so in a

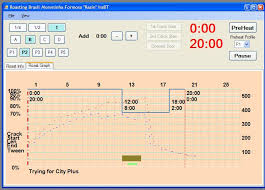

st a batch once a week or so in a  I keep track of my inventory and roast history with a program called

I keep track of my inventory and roast history with a program called  After the appropriate resting period (three days, usually) I grind in a

After the appropriate resting period (three days, usually) I grind in a  Then I pull my shots with a

Then I pull my shots with a  Sunbeam raised the bar with a

Sunbeam raised the bar with a